Dear clients who sent me this article, thank you!

So many of you have written to me, that I have taken the time to post a formal and thoughtful reply. I will respond to the article point by point and picture by picture:

The author, Esther Gokhale, begins the article with this statement:

“Healthy backbends happen at the lowest lumbar level (L5-S1); unhealthy backbends happen higher up in the lumbar spine.”

To which I respectfully disagree. My opinion is that healthy backbends occur with extension distributed throughout the entire spine, with a little extra extension bend at L4-5 (like Esther says), and at T12-L1, as well as C7-T1 and the occiput. These junction points, I refer to as hinge points, because we naturally have a little more range of motion between these spinal segments. The spine is divided into parts and we name the segments as follows:

- The Neck, cervical section, has seven bones and is referred to as Cervical 1 -7. We refer to them as C1 through C7. C1 is the upper neck bone and it articulates with the skull, known as the occiput.

- The Thorax, or thoracic section, is named by the 12 ribs that attach to these vertebral bones. We refer to these vertebral bones as T1 through T12.

- The Lumbar region, or the low back, has 5 vertebral bones and we call them L1 through L5.

- The sacrum is the fused triangular shaped bone which sits between our two pelvic bones, and which the entire spine rests upon.

- The coccyx is our “tailbone” and is a small bone at the very bottom of our spine, deep inside our gluteal folds.

The junctions between these segments inherently have a greater range of motion compared the range between the other individual bones. Ms. Gokhale correctly states that we have more range of motion between L4-5, to which I refer to as the lumbo-sacral junction, but misses the available range at the thoraco-lumbar junction as well as at the occipital (base of the skull) and cervical regions.

Over the years, clients who have habitually performed backbends with all their extension in the lumbar spine (like gymnasts and a lot of serious Iyengar Yoga practitioners) have come to me with spodylolisthesis (pathological slippage) of L4 and/or L5 leading to arthritis, disc injuries, and other joint injuries at this vulnerable segment of the spine.

Again, my opinion is that healthy backbends actually should have the extension distributed over the entire spine. Let’s look at the pictures to see what I mean.

In the first picture, with Cecily back diving into the water, her spine looks OK from T8 (behind her heart) down (inferiorly). However, she has no extension above T7 and superiorly to her head. Her eyes are facing the sky and, in order to safely land in the water without hurting her neck, she needs to be spotting the water. At his point in her dive, her upper back should be extended in a curve to engage her “wings” (scapular stabilizing muscles) to protect her neck and head when she hits the water.

I agree with Esther that the second picture is back bending “unhealthily almost entirely in the upper lumbar spine.” You can see her “hinge” at T12-L1 and her ribs flaring out. If she continues back bending this way, she will most likely end up with an overuse injury at her thoraco-lumbar junction of the spine.

In the third picture, BKS Iyengar is performing “dancer’ pose (Natarajasana). He does have his abdominal muscles engaged nicely and does not have any rib flare. However, the hinge that is noticeable in his lumbar spine makes me cringe. I believe that he should have a little more extension in his thoracic spine to take the fulcrum out of his lumbar spine. This is where I disrespectfully disagree with Esther, who states that this is a healthy backbend. Can you see how flat his thoracic spine is? This lack of curve dumps all the gravity and force into his lumbar spine, causing too much load on his L4-5 segment. Notice how his upper trapezius (neck) muscles are shrugging instinctually to subconsciously lift the load out of his lower spine? His spine is not adequately protected and I believe that habitual practice of this pose with this form will lead to arthritis in the L4-5 vertebrae. Unfortunately, he has passed away, so we may never know if he suffered low back pain.

Picture number four shows the Peking Acrobats hinging in their L4-5 vertebrae and then weight bearing on top of that! This also makes me cringe. A quick google search reveals that the Peking acrobats’ average age is 16 or 17 years old. They begin training at age 5 and join the troupe at age 10. Simple math of averages tells us that these performers are not practicing into their 90’s, like Iyengar. I predict that their spines fail them at a younger age than their peers. I disagree with Esther that these backbends are sustainable. The Peking acrobats are considered “contortionists” who have expanded upon their genetic disposition for hyper-mobile or lax ligaments. They train 6 days per week to achieve these feats. Neither acrobat in the picture has any extension in their thoracic spines. I wonder what they are doing in their 40s and 50s? I predict that they have arthritis in their Lumbo-sacral junctions (the point of hinging and the most strain).

Picture number 5 shows a gymnast who is flaring her ribs (holding her breath at the top of an inhalation) and extending only in her thoracic spine. The author states: “Higher up in the lumbar spine, repeated, sustained, or extreme extension results in wear and tear and injury in the related discs and vertebrae.”

This is misleading. Yes, any repeated, sustained or extreme extension results in wear and tear, but I argue that it is only when we achieve ALL of the motion at one segment, that produces overuse injury, such as in a “fulcrum” at the junctions between the three spine regions. This gymnast is exhibiting what I call a fulcrum at the thoracic-lumbar junction (T12-L1). Her thoracic extension is not unhealthy though. In fact, in the Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy, a research report discusses “impairment of thoracic extension is commonly associated with mechanical pain disorders in this region of the spine.” This directly contradicts what Esther is proposing. We do need extension in the thoracic spine to maintain spinal health. Again, I propose that we need the entire spine to extend during a backbend to sustain the load and distribute it more equally to prevent excessive wear and tear.

Further commenting on this fifth picture of the gymnast, Esther continues: This young gymnast exhibits a classic gymnastics pose, with a significant (unhealthy) sway in her upper lumbar spine. Gymnasts are notoriously prone to back pain and injury.

I disagree that this gymnast has any sway in her lumbar spine. Instead, I see a slight hinge at her Thoraco-lumbar junction (T12-L1) and a complete lack of lumbar extension (her lumbar spine is flat). If I were predict this gymnast’s future injury (because I agree that ‘gymnasts are notoriously prone to back pain and injury’), I see an overuse hinge at her thoracolumbar junction.

Now let’s check out the sixth picture of the dancer back bending against the wall. I agree with the author that “The majority of this dancer’s backbend happens at a single level in her upper lumbar spine…” I see a hinge at her thoraco-lumbar junction T12-L1 and a flare of her ribs. This is a point of extreme flexion and probable over-use injury. I disagree that the lumbar and thoracic extension this dancer is demonstrating is unhealthy, but agree that there is too much at the T-L junction versus “her upper lumbar spine” like Esther states. We both agree that there should be more lumbar curve here.

Here the author discusses a few things. As much as I want to comment on the “J-curve” and the Gokhale Method in general, this reply is already much longer than I anticipated and I will save comments on it for the future. Sticking with backbends and nomenclature, we agree that there needs to be a distinction between upper and lower lumbar curvature. I define these points as the thoraco-lumbar junction (T12-L1) and the lumbo-sacral junction (L5-S1).

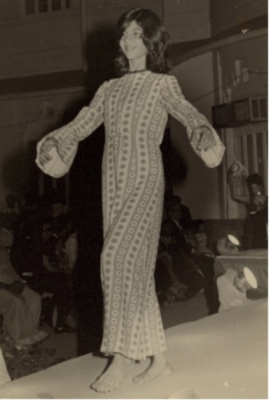

Here is a picture of Esther in 1973 demonstrating what she calls “a significant sway” in her upper lumbar spine. Yes, she is displaying hyperextension at T12-L1 and I agree that habitual posture like this could lead to pain and overuse. Too bad her yoga and dance teachers didn’t know better then. All my clients know to use a broomstick to find their central and neutral spine. I hope they see why now.

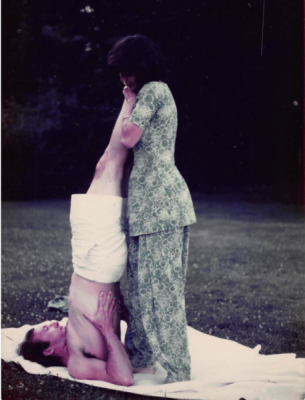

This image is more difficult for me to comment on because of the baggy clothes (I can’t tell what her feet or knees are up to). To my best estimate, it does look like what Esther is calling a “sway” in her back, is her muscular effort of lifting her student’s legs is primarily coming from her upper body (verses her legs and core) which does place unnecessary stress on the thoraco-lumbar and cervico-thoracic junctions.

For a moment, Esther and I agree that to learn how to do a proper backbend, one should begin with the baby cobra, as pictured above. Where we differ is that she is saying that this image has placed all the extension in the L4-5 segment. Actually, this guy above is demonstrating a perfect mini-cobra pose with the extension evenly distributed throughout his entire spine. This person does not display any hinging along the spine and he is not using his hands to force his range. This *is* a good example of a healthy backbend. We just differ in our ability to analyze what his spine is doing. We agree that a significant amount of core strength must be used to anchor the ribs to avoid the hinge in the T-L junction (what she calls the upper lumbar spine).

The picture above shows someone in a bridge pose. I disagree with Esther that this is a healthy backbend. While this woman is engaging her tummy muscles nicely, I still see a rib flare, excessive motion at her lumbo-sacral segment, and she does not have any extension in her upper thoracic region. In other words, her lack of upper thoracic extension is made up for in her effort to achieve the full extent of the pose by extending too much in her lower lumbar region. This woman would benefit from mobilizing her upper thoracic region and by restoring the natural curve in her neck.

Esther has the following comment of the above picture: “This yoga student’s backbend happens at L5-S1 (which is good) as well as the upper lumbar spine (not so good)- her rib cage protrudes slightly from the contour of her abdomen.”

I agree that upper lumbar curve is excessive and agree that this student has a “rib flare” or that her rib cage protrudes. However, I disagree that the excessive curve in her lower lumbar region is good. Instead, I see that this person has tight quadricep muscles and is making up for it with excessive lumbo-sacral extension. This student also lacks any extension in her upper thoracic region and I think that explains her rib flare/protrusion.

I agree with the author that the person in this picture “backbends entirely in her upper lumbar spine (ouch) and we see her ribs lift away from her abdomen a great deal. ” Let’s look at a proper camel pose to see where I think the extension should be distributed:

As far as her spine is concerned, I do not see any hinges or fulcrums in her spinal segments, nor do I see any skin folds indicating excessive extension at any one level. I do see excessive scapular elevation and her lower trapezius should be engaged more to protect her neck, but her form is pretty good overall. Her pelvis is neutral, her ribs are not flared, and her tummy muscles are properly engaged. She is distributing the extension almost entirely along her spine. Can you see the differences in the distribution of extension in these two pictures?

The author concludes with a picture of BKS Iyengar performing an inversion, known as Scorpion (Vrschikasana).

Again, I disagree that this is a healthy backbend. May BKS rest in peace and know that I have extreme reverence for him bringing popularity of yoga to the West. In the meantime, I cringe at the fulcrum in his lower lumbar spine and believe that he would have benefitted from some foam roller exercises to mobilize his thoracic extension range of motion. Here is a picture of someone performing a healthier scorpion pose:

Please note the lack of extreme bending along any segment of her spine. She is practicing ahimsa or non-violence to her spine by not sacrificing safety to achieve the expression of the pose (her feet are not on her head, but her spine is protected.

That said, I would like to conclude with a picture of what I would argue is a healthy backbend to counteract the ones used in the beginning of this comparison. Namaste.